Explore the awe-inspiring journey of Temples in India from ancient cave shrines to the towering gopurams of the South. This detailed guide traces the architectural, spiritual, and cultural evolution of Temples in India through seven transformative epochs—starting from the Indus Valley civilization, through the rock-cut marvels of Ellora and Ajanta, to the intricate Nagara and Dravidian styles that define Indian temple architecture today.

Discover how political dynasties, devotional movements, and regional aesthetics shaped the temples’ structural forms and spiritual significance. Learn how Temples in India were not just places of worship, but also hubs of art, science, music, dance, and community life. From Gupta-era innovations to the Chola empire’s monumental temples, each chapter unfolds a story of faith etched in stone. Whether you’re a history enthusiast, traveler, student, or seeker of sacred stories, this article on Temples in India offers an immersive, insightful, and visually rich experience. Step into centuries of devotion, design, and divine ambition as we decode the legacy of India’s sacred spaces. Perfect for readers looking to understand the soul of India through the evolution of its temples.

Epoch 1: Cave Shrines and Early Rock-Cut Temples in India (2500 BCE–300 CE)

India’s earliest sacred architecture finds its roots in the womb of the earth — literally. The beginnings of temples in India can be traced to cave shrines, which emerged as spaces of deep spiritual meditation and ritual during the prehistoric and early historic periods. These weren’t just primitive shelters; they were meticulously carved into rock faces, echoing both artistic finesse and religious devotion.

The earliest examples include the Lomas Rishi Cave in Bihar, dating back to the 3rd century BCE, with its ornate Chaitya arch — a precursor to later Buddhist temple forms. Many of these early shrines were Buddhist, Jain, or Ajivika, supported by royal patronage like that of Emperor Ashoka and later dynasties.

The Ajanta Caves (2nd century BCE–6th century CE) and Ellora Caves (5th–10th century CE) stand as masterpieces from this era, with elaborate carvings, frescoes, and pillars that hint at the grandeur to come in freestanding temples. These cave temples, though static, radiated dynamic spiritual energy. They formed a sacred blueprint for the monumental temples in India that followed.

This epoch showcases the evolution from natural rock shelters to spiritual sanctuaries, marking the silent but significant dawn of temple architecture in India.

Epoch 2: The Rock-Cut Marvels (600 BCE – 300 CE)

Temples in India during this epoch took on a dramatically different form—carved not from stone blocks, but sculpted into living rock. This era marks the birth of Indian temple architecture as we know it, with artistic ingenuity and spiritual devotion literally chiseling out sacred spaces from cave walls.

The most iconic examples from this period are found in Bharhut, Barabar Hills, Ajanta, and Ellora, where the blend of natural elements with religious function created immersive environments for worship. These rock-cut temples in India were primarily Buddhist in the early phase, but over time, Jain and Hindu cave shrines flourished alongside them. The Barabar Caves in Bihar, dating back to the Mauryan period, are considered the earliest surviving rock-cut structures, showcasing polished granite interiors and harmonious design.

By the time of the Satavahanas and early Chalukyas, temples in India began showing more elaborate features—columns, pillared halls, and narrative sculptures. The Ajanta Caves, for example, are not just places of prayer but storytelling canvases, capturing the life of Buddha with astonishing clarity.

What makes this epoch truly groundbreaking is how it pushed the boundaries of construction—transforming mountainsides into monuments. These weren’t just architectural feats but profound cultural statements about permanence, sanctity, and connection to nature. They also set the stage for the development of free-standing temples, which would emerge in the next epoch.

The rock-cut temples in India remain enduring examples of artistry, patience, and spiritual dedication. They reveal how early India’s temple builders weren’t just architects—they were visionaries shaping the sacred into the very bones of the earth.

Epoch 3: Foundations of Form – The Rise of Free-Standing Temples (300–700 CE)

Following the rock-cut era, temples in India began to shift from being sculpted within mountains to being constructed as independent, free-standing structures. This architectural turning point allowed greater experimentation with scale, form, and symbolism, marking the evolution of temple architecture into a civic and sacred landmark.

One of the earliest examples of this transition is the Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh (circa 6th century CE), dedicated to Lord Vishnu. Built during the Gupta Empire—often referred to as the “Golden Age” of Indian civilization—this temple showcases a square sanctum (garbhagriha), crowned by a simple shikhara (tower), and flanked by elaborately carved panels depicting scenes from Hindu mythology. It laid the template for future temples in India, blending aesthetics with devotion.

![]()

Meanwhile, in the Deccan region, the Chalukyas of Badami introduced a hybrid architectural style, merging northern and southern features. Their rock-cut shrines and early structural temples at Aihole and Pattadakal display experimentation in layout and ornamentation. Aihole, in particular, has been called a “cradle of Indian temple architecture” due to its architectural diversity and innovation.

This epoch also witnessed a philosophical and ritualistic transformation. Temples in India became not just spaces of worship but also cosmic diagrams, designed according to ancient texts like the Vastu Shastra. The mandala-based plans, alignment with cardinal directions, and elevation in layers symbolized the journey from the earthly to the divine.

The rise of free-standing temples in India created a new relationship between sacred space and society. Unlike cave temples, these structures stood in open view—welcoming pilgrims, artists, scholars, and kings. They became centers of art, learning, and community life.

This epoch laid down the essential grammar of temple architecture in India—verticality, symmetry, symbolism—paving the way for the towering gopurams and sprawling complexes that would come in later centuries.

| Dynasty | Architectural Style | Key Temples | Region | Architectural Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gupta | Nagara (Early form) | Dashavatara Temple (Deogarh), Bhitargaon | North & Central India | Early shikhara towers, square sanctum, subtle ornamentation |

| Pallava | Dravidian (Proto) | Shore Temple, Pancha Rathas (Mahabalipuram) | Tamil Nadu | Rock-cut and structural blend, early gopurams, rich carvings |

| Early Chola | Dravidian (Refined) | Vijayalaya Choleeswaram (Narthamalai) | Tamil Nadu | Tall vimanas, axial mandapas, temple complexes |

| Western Chalukya | Vesara (Hybrid) | Lad Khan Temple, Durga Temple (Aihole), Pattadakal | Karnataka | Nagara + Dravidian fusion, stepped towers, ornate doorways |

| Rashtrakuta | Vesara / Rock-cut | Kailasa Temple (Ellora) | Maharashtra | Monolithic structure, vertical excavation, sculptural mastery |

Epoch 4: Sacred Grandeur – The Flourishing of Temple Cities (700–1200 CE)

The period from the 8th to 12th century marks a golden phase in the evolution of temples in India, when temple-building reached new heights in scale, complexity, and regional diversity. This era saw the transformation of temples into grand cultural hubs, surrounded by urban settlements, marketplaces, and festivals that revolved around temple life. Temples were no longer just places of worship; they became the beating hearts of temple cities.

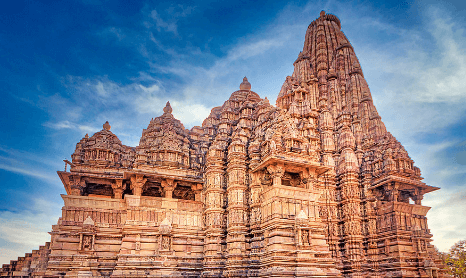

In North India, the Nagara style matured with soaring shikharas (towers), ornate carvings, and geometrically precise layouts. A shining example is the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple in Khajuraho, built by the Chandela dynasty in the 11th century. With its high curvilinear tower, intricate erotic sculptures, and symbolic placement of shrines, it reflects both divine celebration and artistic finesse. This temple and others in Khajuraho demonstrate how temples in India began to embody both spiritual and sensual dimensions.

Meanwhile, in South India, the Dravidian style flourished under the Pallavas, Cholas, and Pandyas. The Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur, built by Rajaraja Chola I in the 11th century, stands as a monumental achievement of Dravidian architecture. With its massive vimana (tower), pillared mandapas, and detailed inscriptions, it is a testament to the political power, wealth, and devotion of the Cholas.

The Western Indian region also saw remarkable development, especially under the Solanki dynasty in Gujarat. Temples like Modhera Sun Temple reflect a fusion of Vedic ritual and cosmic symbolism, showcasing how solar alignments influenced temple design.

This epoch was also characterized by the rise of temple patronage by monarchs, who saw temples as political symbols and vehicles of cultural unification. The temples in India from this time reflect not only architectural genius but also the socio-religious dynamics of a deeply stratified society.

Through elaborate carvings, ritual spaces, and alignment with celestial cycles, this period defined the aesthetic and spiritual zenith of temple architecture in India, setting standards for centuries to come.

Epoch 5: Resilience and Revival – Temples in India Amid Turbulent Times (1200–1700 CE)

The era between the 13th and 17th centuries marked a significant transition in the history of temples in India, shaped by political upheaval and cultural synthesis. The expansion of Islamic rule across much of the subcontinent brought new architectural forms, administrative systems, and occasionally, conflict with existing Hindu religious structures. Yet, what emerged was not merely destruction, but also adaptation, resilience, and regional revival of temple architecture.

In regions like the Deccan, Vijayanagara Empire (14th–17th century) led a grand resurgence in temple building. Rulers like Krishnadevaraya commissioned monumental temples that reflected both religious devotion and imperial power. The Virupaksha Temple at Hampi is a shining example—with its towering gopurams, sprawling courtyards, and intricate reliefs celebrating Hindu deities and epics. These temples were not just spiritual sanctuaries, but fortresses of culture, preserving language, art, and identity amidst shifting political tides.

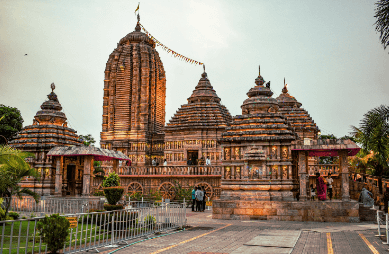

In Odisha, the Sun Temple at Konark (13th century), designed as a colossal chariot of the Sun God, demonstrated the continuity of temple patronage and the evolving symbolic narratives in temple architecture. Despite facing natural decay and invasions, the structure remains one of the most iconic temples in India, both for its artistic vision and engineering prowess.

Even in regions under Sultanate or Mughal influence, like Rajasthan and Gujarat, temple construction quietly persisted. The Dilwara Temples of the Jains on Mount Abu, built during the 11th to 13th centuries, highlight how different faith communities contributed to the continuation of sacred architecture. The marble work, polish, and geometric perfection remain unmatched even today.

Despite periods of desecration, temples in India during this epoch became symbols of resilience. Local communities often rebuilt shrines, preserving ritual practices and oral traditions. While Indo-Islamic architecture was flourishing in urban centers, rural and regional temples continued evolving in form and function, quietly carving a space for continuity amid transformation.

This epoch, therefore, stands not only for survival but for a creative revival—where temples in India became expressions of cultural resistance and spiritual perseverance.

Epoch 6: Colonial Shadows and Sacred Stones – Temples in India Under British Rule (1700–1947 CE)

The colonial era brought unprecedented political, economic, and cultural shifts to the Indian subcontinent, and temples in India were not immune to these changes. While the British Raj did not pursue systematic temple destruction, the indifference of colonial governance and the prioritization of Western institutions contributed to the marginalization of temple spaces in public and civic life.

Yet, temples endured—not as static relics, but as evolving sites of resilience and reform. This epoch saw a dual narrative: the neglect of ancient temples by colonial authorities, and the parallel rise of temple patronage among local kings, reformers, and nationalists seeking cultural preservation.

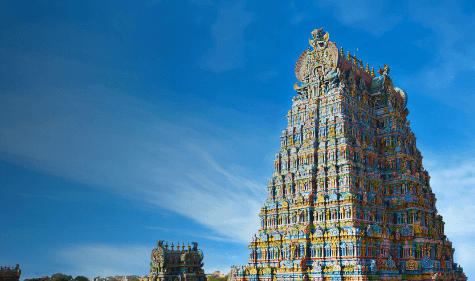

The Madurai Meenakshi Temple and the Jaganath Puri Templecontinued to attract pilgrims, while local rulers such as the Marathas, Wodeyars of Mysore, and Gaekwads of Baroda restored and patronized temple complexes in defiance of colonial dominance. Temples in India during this period thus became symbols of cultural identity in an era of foreign rule.

At the same time, Indian reformers and religious leaders—including Swami Vivekananda and Dayananda Saraswati—invoked temple culture as a repository of Indian values. Their revivalist discourse brought new attention to Hindu institutions and sparked restorative efforts to protect temple heritage. The emergence of temple trusts, often run by devotees or local elites, became instrumental in preserving temple management independent of colonial interference.

Moreover, the British fascination with India’s ancient past led to the formation of institutions like the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1861. While originally focused on Buddhist and Islamic monuments, the ASI gradually turned attention to ancient Hindu temples, documenting and protecting sites like Khajuraho, Ellora, and Mahabalipuram. Ironically, while the colonial state weakened temple patronage systems, it also facilitated early heritage conservation.

This period saw temples in India quietly transform from exclusive religious spaces to national cultural icons. They began to symbolize not just devotion, but resistance, identity, and continuity—threading a connection between sacred traditions and the emerging Indian consciousness.

As India approached independence, temples stood tall—not as passive monuments of the past, but as active guardians of spiritual heritage and cultural pride.

Epoch 7: Revival and Innovation – Temples in India After Independence (1947–Today)

The story of temples in India did not end with colonialism—it entered a new chapter marked by freedom, modernization, and spiritual renaissance. In the post-independence era, temple architecture began to blend traditional designs with modern engineering, symbolism with statecraft, and sacredness with tourism.

This epoch witnessed both the revival of ancient temple complexes and the creation of monumental modern temples, reflecting India’s growing confidence in its cultural identity. Governments, temple trusts, and private citizens joined hands in renovating old temples, expanding pilgrimage circuits, and promoting heritage tourism.

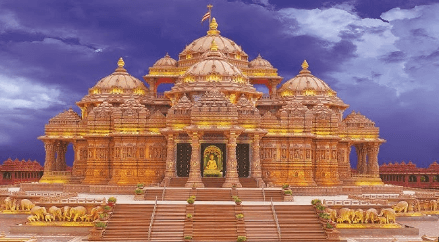

One of the most iconic post-independence temple projects is the Akshardham Temple in Delhi (completed in 2005). This sprawling complex, built in pink sandstone and white marble, fuses traditional architectural styles from across India with multimedia exhibitions, musical fountains, and cultural displays. It demonstrates how temples in India are not only spaces of worship but also platforms for cultural education and national pride.

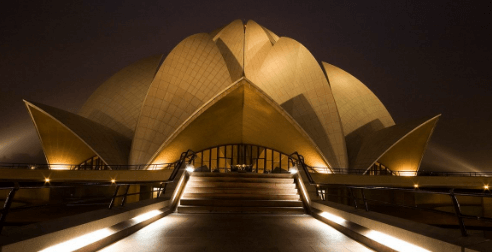

The Lotus Temple in Delhi, built by the Bahá’í community in 1986, marks a notable architectural innovation. Its flower-like design and open-door policy to all religions show how modern Indian temple spaces can embrace spiritual inclusivity and artistic modernism.

Further south, the Sripuram Golden Temple (2007) in Tamil Nadu presents a fusion of Vedic tradition with gold-clad opulence, attracting global attention. Meanwhile, temples like the Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Kerala, with its revealed treasure chambers, continue to astound the world with their ancient grandeur and mystical aura.

A parallel development has been the emergence of spiritual megacenters like ISKCON temples, which now dot cities across India and the globe. These temples blend Gaudiya Vaishnavism with clean aesthetics, community kitchens, and international outreach, giving a global face to Indian temple culture.

In recent decades, technological advancements and architectural engineering have enabled the construction of massive temples like the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, a project rooted deeply in national history, politics, and faith. Scheduled for completion in the mid-2020s, it epitomizes how temples in India today are tied not only to spirituality but also to the nation’s socio-political narrative.

In essence, the post-independence period has seen temples in India evolve into dynamic centers of worship, heritage, and public discourse. They have become symbols of continuity and creativity—sacred spaces that reflect India’s ancient soul and modern spirit.

Conclusion: Timeless Temples in India – A Sacred Journey Through the Ages

The story of temples in India is a journey through 7,000 years of culture, devotion, and architectural brilliance. From the earliest cave shrines of the Indus Valley to the soaring gopurams of South India and the marble wonders of modern temple design, every structure tells a story—not just of gods and rituals, but of people, politics, art, and innovation.

Temples in India have never been static. They’ve transformed across dynasties and epochs, adapting to new philosophies and technologies while staying rooted in ancient traditions. They served as places of worship, centers of learning, guardians of classical art, and community anchors. Even today, they draw millions—not just as spiritual sanctuaries but as living symbols of heritage and identity.

In the global era, Indian temples have crossed borders, becoming cultural icons and sources of inspiration around the world. Their legacy is not just about religion; it’s about resilience, beauty, and belonging.

As we preserve, study, and continue to build temples in India, we honor more than history—we celebrate a civilization that continues to rise, inspire, and radiate through stone and spirit.

MCQ QUESTIONS WITH EXPLANATION

1. Which dynasty is most closely associated with the construction of the Kailasa Temple at Ellora?

A. Gupta

B. Chola

C. Rashtrakuta ✅

D. Pallava

Explanation:

The Kailasa Temple at Ellora is a monolithic rock-cut marvel carved under the patronage of the Rashtrakuta dynasty, especially during the reign of Krishna I in the 8th century CE. It showcases exceptional engineering and sculptural skills, representing the Vesara style.

2. The Vesara architectural style is best described as a blend of which two styles?

A. Indo-Islamic and Nagara

B. Nagara and Dravidian ✅

C. Dravidian and Gothic

D. Buddhist and Jain

Explanation:

The Vesara style is a fusion of Nagara (North Indian) and Dravidian (South Indian) architectural styles. It flourished especially under the Western Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas, visible in temples at Aihole, Badami, and Ellora.

3. What was the main architectural contribution of the Pallava dynasty to temple building in India?

A. Gopuram towers and temple tanks

B. Rock-cut and early structural temples ✅

C. Use of white marble in temples

D. Domed ceilings in sanctums

Explanation:

The Pallavas pioneered rock-cut temples, like the Pancha Rathas and Shore Temple at Mahabalipuram, blending natural rock formations into early Dravidian-style structures, laying the foundation for future South Indian temple design.

4. During which epoch did free-standing temples in India first begin to appear prominently?

A. Epoch 1: Cave Shrines and Early Rock-Cut Temples

B. Epoch 2: The Rock-Cut Marvels

C. Epoch 3: Foundations of Form ✅

D. Epoch 5: Turbulent Times

Explanation:

Epoch 3 (300–700 CE) marks the rise of free-standing temples in India. This shift from rock-cut to structural temples can be seen in examples like the Dashavatara Temple in Deogarh, built during the Gupta period.

5. What does the term “gopuram” refer to in the context of temples in India?

A. Sanctum sanctorum of Jain temples

B. Main dome of a Buddhist stupa

C. Ornate entrance tower of a South Indian temple ✅

D. Meditation chamber in Himalayan cave shrines

Explanation:

A gopuram is a tall, ornate entrance tower typical of Dravidian (South Indian) temples. Introduced during the Pallava period, it became a defining element in later temple cities like Madurai and Thanjavur under the Cholas and Nayakas.